Essays

“The Master of Allusion & Her Tangled Web: Citation/Tagging as Inclusive Gratitude”

Submitted to the ALSCW panel “Allusion as Exclusion and Inclusion: Only Connect?” but they saved me from myself by not letting me present 3 papers at one conference!

Abstract:

Allusions sound intimidating, but it’s an illusion. The problem for students and lay readers is that we send them to hunt for references to texts like the Bible or Greek myths that, for better or worse, they aren’t familiar with in the way (educated, white, male) readers were in earlier centuries. My solution: we can help them make connections through annotations, citations, and tags, telling them where to look. T.S. Eliot modeled this practice with his notes accompanying The Waste Land, a masterwork of allusion comprehensible because he gave us the key (and it really is accessible with his notes; I’ve taught it to high school sophomores!). Citing our literary and cultural networks is super easy, barely an inconvenience in the days of the Internet, accomplished with the click of a button, so this is a gift we can afford to give to our students and readers.[1]

This kind of signposting doesn’t only help us get readers where we want them to go. It also allows us to pay homage to the works and artists we love and that have shaped our thinking. Really, allusion is just a fancy name for the associations we constantly make in our thoughts, the trail left behind when one thing reminds us of another. All together, these connections make up what Jung called the collective unconscious, but allusions, when cited, allow us to celebrate the nodes and nexuses most important to the way we see the world. By using allusion to situate ourselves in this tangled web, we also define who we are. Jesus was the master at this, living his life as an allusion to the stories of the Hebrew Bible to show us what God is like and the role He wants to play. Allusion allows us both to thank and connect to the people whose art we admire (it’s why I keep tagging Lin Manuel Miranda in my Instagram photos; I dream of interviewing him about his work/becoming besties) and to signal our own affiliations (always revealing, since we can only allude to what we ourselves read/watch; we are what we eat, metaphorically). A tag is the work of the graffiti artist, who leaves their mark on the wall for all to see and thus permanently inscribes their perspective on the landscape. Through allusion, we create a reciprocal relationship with the art we reference, entering a chat and creating a receipt that changes both our work and theirs for good. Of course, we’ll never cite or catch them all, because pieces of art constantly sound with unexpected resonances, the humanities equivalent to quantum entanglement that binds separate particles together. And that’s the fun of allusions; those of us who have mastered them get to go on Easter egg hunts, and we never know what goodies we might find! To see an example of the kind of allusive tagging I’m talking about, check out the archive of my Juneteenth party on funoverfear.org, the website of the larger project I’m working on. It might help you spot some of the many uncited allusions in this abstract (including in the title); enjoy!

[1] Hot take: the nitpicky citations that our students hate learning and I hate grading are on their way out, now that we can easily add a tag or link online.

“Why I Still Care: ‘No Coward Soul Is Mine’”

Submitted to the 2025 Victorians Institute Conference: “Victorian Studies: Who Cares?” but REJECTED for being “too personal.”

Abstract:

I last presented at Victorians Institute in 2018. I was months away from finishing my PhD at Princeton, preparing to apply for jobs and postdocs, sure my future in Victorian Studies was bright. Now, seven years later, the picture looks very different. I never got an academic job. When I pivoted to teach high school, I discovered that many schools no longer teach British literature at all. And after several years teaching in the midst of the COVID pandemic, I burned out. I’m currently unemployed. It might seem like our field has failed me.

However, when my mom died in 2021 and I stood before a church full of mourners, I took off my mask and read Emily Brontë’s “No Coward Soul Is Mine.” My world was falling apart, and I had no words of my own to express my emotions. Yet I knew instinctively where to turn. Brontë’s poem was a life raft, giving me something to hold on to as the waves of grief broke over me.

In this essay, blending memoir and literary analysis, I will examine the lasting connection in Victorian literature between faith and feeling. Drawing on the work on scholars like Charles LaPorte (The Victorian Cult of Shakespeare), I will consider how the Victorians’ devotional relationship to poetry, often elevated to

sacred text as Biblical authority waned, still shapes our experience and understanding of emotion today.

Books

Mirror, Mirror: How I Did Disney Therapy and Learned to (Be) Hope blends literary criticism and memoir to explore the psychological possibilities opened up by identification with Disney princesses, focusing on post-2010 princesses, broadly defined. It’s based on my own experience of doing “Disney therapy,” using Disney characters to conceptualize the “parts” or sub-personalities described by Richard C. Schwartz in his Internal Family Systems model and to plot narrative arcs to help my parts heal. People often label their parts (ie “my anxious part”), but imagining them as characters instead empowers us to think about what the characters we identify with needed to learn and then apply the lesson to our own lives. Basically, I’ve decided the modern Disney princesses are my role models and now take all my life advice from Disney movies; it’s working out for me!

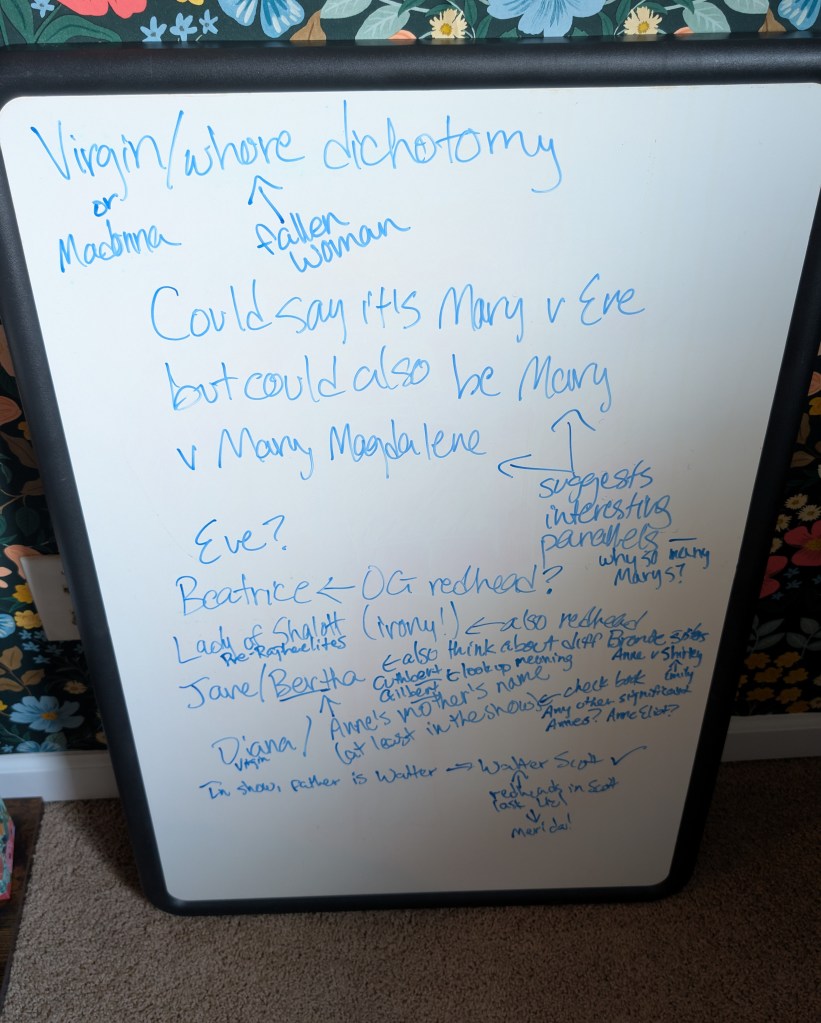

Daughters of Eve: Literary Genealogies

How to Argue: Templates for Teaching Writing

Good Intentions (a memoir)